This post is about a style of knife that I’m sure most of you are familiar with, the emännänveitsi or woman’s knife. I have also seen it called a hostess knife and Viking knife. It is a simple and practical knife that is attractive none the less. I like it because it comes in various forms decided on by each puukkoseppä, because of it’s humble beginnings and it’s place in history.

Federico Buldrini has been researching the emännänveitsi and has written an excellent summary for Nordiska Knivar. I hope you enjoy it as much as I have.

Federico Buldrini:

Hand forged all steel “blacksmith’s knives”

“Since they are often referred to as “woman’s knives” there are actually debates about them being used only by women, while they were most likely simple and rather inexpensive working knives: the amount of metal is just a bit more than for an equally long blade, while the amount of work is much less then what’s needed for crafting a complete knife with wood handle and leather sheath. The price was low also because they were often forged from iron, instead of then expensive steel, this allowing them to be forgotten over a fire without spoiling the heat treatment.

The exact origin of this knife pattern is lost in the fog of the centuries, but certainly the oldest specimens are dated to the Iron Age (500-12 B.C.) and are related to Celtic and Germanic tribes living in central Europe.

The first specimens coming from northern countries are from Denmark Iron Age burials and already show many of the style variations existing today.

A few more specimens dated to the Viking Age and Middle Age come from Gotland island (Sweden), Tensberg (southern Norway), Pielavesi and Saarijärvi (central Finland).

This knife pattern was most likely exported to the Fennoscandic peninsula, together with the Germanic metallurgic and smithing knowledge, during the Migration Period (400-700 A.D.) not only by the tribes sailing north, but also by traders that were increasing their power during this age of movements and contacts with other populations.

During the Viking Age (700-1066 A.D.) these knives probably spread, thanks once more, to trading due to their handiness in daily household duties and their low price coming from their easiness to be crafted.

Both in Scandinavia and Finland women also had their own, smaller, sheath knives but that’s another story.

Let’s give some background:

During the Migration Period Danes sailed from Jutland towards Sweden, some settled down in Scania and there was actually a time in Danish history, during XI century where Denmark, Norway and England were ruled as a single reign, for almost twenty years, under the power of Canute the Great.

During the Viking Age, from Swedish colonies some tribes moved to Norway and, subsequently, created additional colonies on Fær Øer Islands, Iceland and Greenland. It may seem impossible, but actually do exist, in Greenland and Alaska, very few specimen of Inuit iron ulus looking much like some of the Iron Age Danish specimen which have the tang completely bent over the slightly curved blade.

On their part Swedes moved, explored and traded towards Finland, Russia and Orient all the way down to Constantinople. As for the rest of Nordic countries, the Iron Age started in Finland around 500 B.C. From about 50 A.D. we have proof of trades with Baltic and Scandinavian tribes; commerce with Vikings started during the VIII century and by 1157 Finland was under the crown of Sweden. This signified also the beginning of Finnish written history.

There are only few Middle Age museum specimens of blacksmith knives, leading some to doubt their authenticity, but the explanation is probably more simple than expected.

In Dark Ages Fennoscandia, mounds burials were very scarce and only for very wealthy men and women. Also, for some time dead were only cremated, with their entire outfit, so burial findings show mainly jewelry, amulets and weapons, with very few exceptions.

Daily tools were most probably reused by the other family members or reforged into something else. Also, being usually forged from iron, the harsh conditions they may have been put to in the burial mounds could have been enough to destroy the majority of eventual buried specimens. Danish Iron Age specimens were, on the other hand, buried in bog like soil that, being almost completely anoxic, is perfect for conservation.

You may find these knives called in bit different ways around Fennoscandic peninsula, but all names are fairly translatable as “woman’s knives”

Denmark: kvinderkniv

Norway: kvinnekniv

Sweden: kvinnokniv

Finland: emännänveitsi

So, who were those Viking women?

Among Norse clans the wife of a free man usually wore an ankle length linen under-dress, with the neck closed by a brooch. Over it she wore a shorter woolen dress suspended by shoulder straps fastened by brooches. From these brooches hung a few chains to which were attached a pair of scissors and the keys of the chests where family heirlooms were kept. A pouch and a belt knife could be carried on a thin leather belt or hung from another of the chains.

It’s also worth knowing that, even if Vikings accepted the fact that a rich man could have a wife and a few concubines at the same time, and politics was essentially a man’s duty, the families usually had extremely tight bonds and it was a recognized fact that the house and family fate was largely in the women’s hands. While men were taking care of politics, trade, crafts and agriculture, women had to take care of children, house duties, making clothing and, if the husband was away, they had the right to take charge of the family business too.

In addition very strict laws existed concerning respect for women, some forbidding men to beat them. A slapped wife had the right to ask for divorce and plenty of economical compensation, since marriage agreements were considered just another kind of trade. All this allowed Viking women to have a great influence in the family decisions and have a much stronger role in the society compared to what it was like in the rest of Europe during the same period.

Finnish women’s clothing fashion was quite similar to the one described above. Though, instead of the woolen dress with shoulders suspenders, Finnish women used to wear an apron with decoration on the lower part, and a short cloak fastened by fibulas. There was also the same habit of using chains to carry jewelry and tools.

In the beginning Finnish population was fragmented in various tribes without a single law system. Their contacts with Scandinavian people influenced Finnish society that started to have regional governors to administrate the law, instead of the annual Viking “Thing” meeting, until the advent of Swedish domination.

As in Viking society women were subjected to the father or the husband, while keeping a remarkable liberty and free will for the time. Caretaker of hearth and home, nurses for the children, they were highly respected,

while expected to be faithful wives and loving mothers. Men on their side were expected to be kind and protective. There wasn’t a real law against violence on women, but house violence has been always very strictly disapproved in Finnish society. Beating a wife was accepted only in very religious families and only if she demonstrated to be particularly rebellious, disrespectful or unfaithful. Still beating was used as a very last remedy.

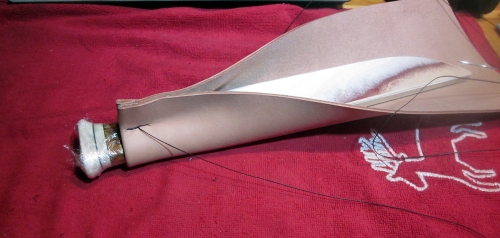

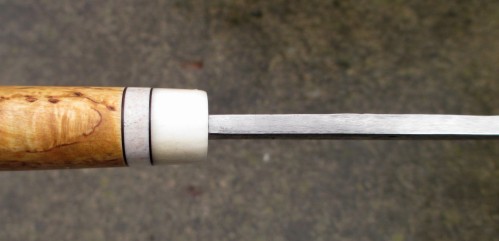

The basic shape and style of these knives have remained rather the same during the centuries.The blade has a flat section and may have either a sharp point or a blunted one. What makes this pattern immediately recognizable though is the variously bent tang. You may see specimens with just a ring at the end, some others with tangs bent upward or downward and others with the end of the tang itself reconnecting with the blade’s heel.

In Finland woman’s knives had almost always been flat pointed and the ring at the end of the tang was curved upward. The specimen with sharp point and rind downward are called viikinkiemännän veitsi (viking woman’s knives) due to the more Scandinavian style. Those are small details but they were part of the old Finnish style. From this basic shape every smith can add any metal twisting his inspiration may call. The dimensions change in relation to the intended purpose; the bigger knives being for bread and meat, the smaller ones for basic kitchen and domestic duties.

Sheaths too can be very different. The smallest knives are usually carried around the neck in a small leather sheath while bigger ones can have either a leather or birch bark strips kind of belt sheath. In the end, everything depends on the smith.

A special thank you to Illka Seikku for his help in preparing this article. F.B.”

Thank you Federico and all the puukkoseppä!

A selection of contemporary emännänveitsi: