Merry Christmas, Happy New Year and Happy Holidays to all the readers.

Henri Tikkanen

Mikko Inkeroinen

Jari and Arto Liukko

Eero Kovanen

Jukka Hankala

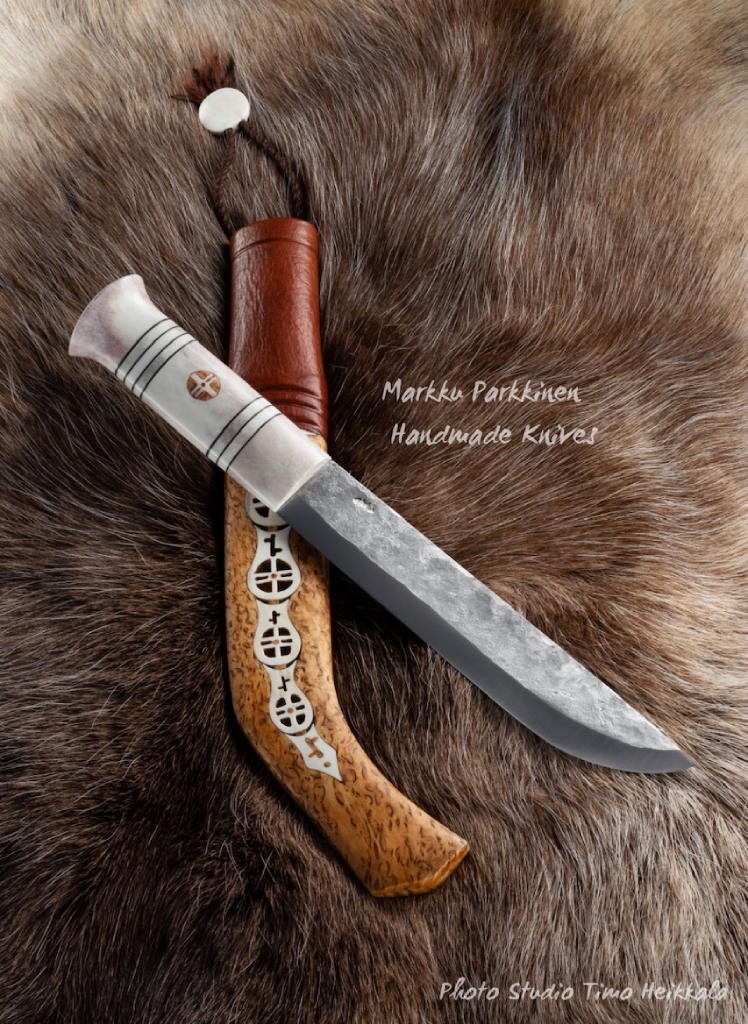

Markku Parkkinen

Anssi Ruusuvuori

Saku Honkilahti

What follows is a series of pics taken by our Norwegian friend Sverre Solgård while crafting a knife for his son using a blade by Swedish knifemaker Pär Björkman. I adapted the text from the Norwegian original. – Federico Buldrini

The stitching method Sverre used was developed by Aasmund Voldbakken in the late 1970s and then got a major breakthrough in the 80s: knives with this style of sheath and stitching have been crafted mostly only after 1984, while the paternity of Voldbakken has been since almost forgotten.

This style doesn’t need the sheath to be stitched around the knife or a liner and allows for great personal expression, plus is quite easy to learn and no particularly specialized tools are required. All the wet forming is done after the sheath is completed.

For Norwegian speaker Sverre suggests checking out Per Thoresen book “Kniver og knivmakere” and two Sigrunn Lie Brattekås books “Bjørn Kleppo – Den moderne knivmakars far” and “Knivkunstnaren Gunnar Omdal”.

Posted in Uncategorized

Text and pics by Reno Lewis

Mikko Inkeroinen is one of twelve FNBE certified Puukkoseppämestari, and he lives and works in the town of Mikkeli, in Eastern Finland. This specific knife is a beautiful take on a Tommi puukko, with forged finish flats, curly birch and a beautiful mottled brown sheath.

Mikko has mentioned before that Tommi puukko is his favourite knife model, so I was excited to see his take on this traditional model with a bit of a twist. To directly quote Mikko’s interview here on the blog:

“I think my mission is to show people that tools can be also beautiful. That is the reason why I make knives. My motto is “form is more important than level of finishing”. My favourite knife model is Tommi-puukko.” -Mikko Inkeroinen, 2013.

Blade

Length – 94mm

Width – 19,8mm at the bolster

Thickness – 3,5mm at spine; 4,3mm at bevel junction at bolster, 2mm at bevel junction at tip.

Tang – 3,5×3,2mm at peening, roughly 15mm wide at bolster

Steel – Böhler 115CrV3 Silversteel

Bevels – Flat

Edge angle -17°

HRC – ~ 60 HRC

Handle

Length – 116mm from bolster to peening, wood is 103mm

Width – 28mm max.

Thickness –22mm max.

Weight

Knife – 96g

With sheath – 146g

This is a somewhat different take on a Tommi puukko, having forge finished flats and a forward canted front bolster. The sheath is also more reminiscent of the war era Tommi puukkos with more subdued colors, compared to the traditional red and black sheaths. It makes for a very handsome package and could as easily pass for a dress knife as it could a serious working tool.

The blade is hammer and anvil forged from a round bar of Böhler 115CrV3 Silversteel with a rhomboid cross section and strong distal taper. The bevels are flat ground to zero at 17°. The blade has a very gradual, sweeping belly which makes for a very powerful cutter which is also capable of great finesse.

The handle is made from curly birch with a 3,75mm thick brass bolster and a 9,75mm long brass pommel. There are no spacers of any kind between the wood and the brass, showing excellent skill in fitting the two materials together. It arrived to me well oiled, and in pristine condition. The handle has a tear drop cross section in the front, a fairly generous midsection palm swell, and turns into an oval cross section towards the pommel, with a distinct taper in both height and width from the center out towards the bolster and pommel. The sections of the handle closest to the bolster and pommel feel a hair too narrow for my hands and might prove to be uncomfortable during powerful cutting.

The sheath, while not the traditional red and black, bares the same distinctive Tommi embossing. It is made from 2mm thick cowhide, with a box style lesta made from what looks to be either birch or alder, carved and sanded to shape. The entrance of the lesta is properly beveled and makes for a very easy to use sheath. The surface of the leather has a polished clear coat, and the inside is left untreated. It is hand saddle stitched with a waxed, braided thread of about 1mm diameter. It is then back-stitched three times and locked off. The sheath also bears Mikko’s makers mark and initials. The belt loop is attached by a brass ring.

First impressions were very good overall. The knife arrived with perfect fit and finish, with a good polish and a well-oiled handle. The bolster to blade fit is perfect, the fit between the bolsters and wood is also perfect, and the fit in the sheath is snappy and tight, without being too tight. The edge, while ground to zero, needed some work on a 6k stone before stropping to bring it up to a usable edge. The tip specifically was quite blunt, but it was easy to tune up in only a few minutes.

In use

This is a somewhat handle heavy puukko, with the point of balance roughly 30mm behind the front bolster. This makes for a very lively and easily controlled blade.

As mentioned above, the edge needed a little bit of work out of the box to be ready for use. A few moments working the very apex on a 6k King KDS stone and finishing on BRKT Black and FlexCut Gold strops had the edge whittling hair with ease.

Beginning with a basic silver birch brand spikkentroll. This wood has been seasoned for 8 years. I noticed a little bit of resistance while making shallow cuts, but little to no resistance making very deep and powerful cuts. The knife left a glossy finish while cutting both with and against the grain. Similarly, the knife bit deep and I felt no significant resistance while freeing the troll from the rest of the branch and flattening the base.

No loss of bite, still rough shaving with no damage. 5 passes FlexCut Gold, back to original shaving edge.

Next up is a simple wizards face. This is only the second time I’ve carved this particular piece, which really let me get a feel for the knife, using different grips and techniques to complete the work. I noticed great control while making long stock removal cuts. Very good aggression and bite while making stop cuts against the grain. The shallow belly and pointy tip was very intuitive to work with here, and made for very easy work. Using a pinch grip was very natural feeling while making stop cuts, as was using a thumb assisted reverse grip. In all, this puukko did very well at this job.

The spine is nicely rounded and polished and was very comfortable to use with an offhand thumb assist while carving.

The knife maintained consistent aggression and bite throughout carving, and would still irregularly shave after the fact, with no damage. 5 passes gold, back to original edge.

Next up is a simple spatula. Like with the wizard, this is only the second time I’ve attempted to carve this piece. The internal curves present a very good challenge to a thin, hard edge.

I split a flat blank out of a seasoned round of Big Leaf Maple, which is about as hard to carve as Silver Birch, just a little more fibrous. The blank split a little thicker to one end, and instead of using a hatchet to thin it out, I decided to put the Tako-Tommi to the test by doing all the stock removal with only the knife.

Very good power making heavy stock removing cuts while thinning the blank down. I also noticed that the blade did not tend to get stuck even if I attempted to take too large of a bite. It did well in this job.

While making the more powerful stock removing cuts, I noticed that the handle nearest the pommel tended to press somewhat painfully into my pinky finger, I believe this is due to how tapered the handle is at both the front and back. Aside from this, the handle indexed very well, and was otherwise very comfortable to use in every grip I needed.

The blade had very good finesse on the inside curves and maintained very good bite and aggression until the very end, where I noticed a sudden distinct lack of bite while beginning to make finishing cuts, as the blade began to jump and skitter, leaving an uneven finish.

At this point I stopped and gave it 5 passes on FlexCut Gold, and the edge came back to life.

After making the finishing cuts, the edge would no longer shave, but suffered no damage. 10 passes gold, back to original shaving edge.

Conclusions

The Tako-Tommi is, in my opinion, a beautiful example of a unique take on a Tommi puukko, without losing sight of its origin. This knife excels at making powerful, deep cuts, but loses nothing when it comes to finesse work thanks to the thin grind, distal taper and shallow belly with a distinct, pointy tip which was perfect for detail work. Both the knife and the sheath are as well thought out as they are well made.

The blade is very well done and held up very well to powerful stock removing cuts, torquing and scraping cuts, and never failed to strop back during use. The shape lends itself very well to both powerful cutting, as well as finesse work with the pointy tip. The handle, while perhaps a tad narrow in certain areas, functioned beautifully with great indexing and only presented signs of fatigue during the most powerful cuts. I noticed no other signs of hotspots forming, or fatigue in any other grip.

In all, a very well made Tommi puukko and sheath with a handsome, somewhat rustic appearance, balanced by a very high level of craftsmanship and fit and finish.

Posted in Uncategorized

Text and pictures by Reno Lewis

He originally posted on the BushcraftUSA forum

https://bushcraftusa.com/forum/threads/pentti-kaartinen-arki-tommi-puukko.313204/

following the review style of the blog and did such an incredible job that I asked him the permission to upload it here as well.

– Federico Buldrini

Despite days of searching, I couldn’t seem to find much information about Pentti Kaartinen online save for a few old forum entries praising his work and some mentions in Finnish language wiki pages and news articles. His own website is fairly dated, very simple, and only lists his phone number as contact, presumably only in spoken Finnish. He is, however, mentioned in every book on the subject I own.

Below are two excerpts from Lester C. Ristinen’s book The Collectable Knives of Finland (which I personally recommend to anyone interested in the subject).

“There are many master of the Tommi-puukko in East Central Finland. Knife collector Jorma Saarinen noted at least 26 knifemakers in the area and there are many more such as J. Vayrynen, Mauri Heikkinen and Pentti Kaartinen. Not only do Mauri Heikkinen and Kaartinen make top of the line Tommi Puukkos, they also deviate into modern day Tommi versions with exotic woods to complement great sallow root burl handles and custom sheath that are very pleasing to the eye of a connoisseur.”

“…Award winners have been Antti Kemppainen and Pentti Kaartinen.”

The following quotes are selected excerpts from a Finnish Living History Wiki page by the name ‘Aineeton Kulttuuriperintö’, translated into English. A link to this page is here: https://wiki.aineetonkulttuuriperinto.fi/wiki/Tommi-puukon_valmistaminen

“In 2002, the traditional Tommi knife manufactured by Pentti Kaartinen from Hyrynsalmi represented a Finnish knife and craftsmanship at an international design fair in Tokyo.”

“When it was noticed that Tommi’s idea of the shape, quality and nomenclature of the knife began to go wild, the Tommi Knife Tradition Association established a standardization committee formed of experts. On her behalf, Pentti Kaartinen made the model Tommit, which is on display in the Tommi-knife exhibition at Hyrynsalmi Municipality.”

“Tommi knives have won numerous Finnish championships and first prizes in other Nordic countries. In 2002, the Tommi knife represented Finnish handicrafts at the international design fair in Tokyo. Tommi, made by Pentti Kaartinen, a blacksmith from Hyrynsalmi, has been on display alongside the works of Alvar Aalto at this fair. My Tommi knife has been donated to President Urho Kekkonen, President Mauno Koivisto and President Sauli Niinistö, among others, as well as to several foreign statesmen. President Kekkonen also used to give Tom as a gift on his travels.”

Below is a short excerpt from a document from the Suomen Puukkoseura, mentioning Kaartinen’s place as a bladesmithing instructor at the Hyrynsalmi College. Mentions of Kaartinen are between pages 35 and 37. Link: https://suomenpuukkoseura.fi/suomalainen_ja_puukko.pdf

“New blacksmiths are born, for Pentti Kaartinen holds Tommi’s course at Hyrynsalmi Citizens’ College, which has students also flickered with prize places in the Finnish Championships in Fiskars.”

Here is a link to a news article directly interviewing Pentti Kaartinen: https://www.kaleva.fi/tyokalusta-kasvoi-perinnetaideteos/2478769#kommentit

A translated excerpt from the above link reads:

” “Tommi’s standard defines many dimensions. They are derived from old Toms, whose model has been modified by the use that has been going on for generations,” says Pentti Kaartinen, a blacksmith living in Letuskylä, Hyrynsalmi.

Kaartinen is not a relative of blacksmiths, but the man is one of Tommi’s best creators. The matter has been tested many times in competitions as well.

“The Finnish championship has come five times. I can’t send my knives to the competition anymore, that thing has already been seen,” Kaartinen laughs. “

By all accounts, the man seems to be a rather omnipresent name in the Hyrynsalmi knife making tradition, and seems to be largely praised for his work with some of his pieces being on display at the Hyrynsalmi museum.

Recently, a few pieces of his became available on Lamnia, and I decided to purchase one. Some years ago I wasn’t a big fan of Tommi puukkos, but I’ve found myself becoming more and more fond of them lately, quickly becoming one of my favorite models.

A few days after placing my order, the knife arrived to me in Canada from Lamnia in Finland.

Blade

Length – 96mm

Width – 19mm

Thickness – 3,2mm at spine; 3,9mm at bevel junction at bolster, 2.5mm at bevel junction at tip.

Tang – 3,5×3,5mm at peening, roughly 12mm wide at bolster

Steel – Böhler K510 Silversteel

Bevels – Flat

Edge angle -17°

HRC – Unknown, likely 61-62 based on in use tests.

Handle

Length – 113 from bolster to peening, wood is 101mm.

Width – 27,5mm max.

Thickness – 20mm max.

Weight

Knife – 85 g

With sheath – 145 g

The knife is a classic Tommi, with a hammer and anvil forged Böhler K510 Silversteel blade, curly birch handle with sand cast pommel, with single birch bark spacers between the wood and brass.

The blade is a rhomboid profile with a distal taper, flat ground 17° bevels to zero, save for the final stropped edge.

The handle is made of curly birch with a 2,8mm thick brass bolster, and a sand cast brass pommel which also appears to be filed to shape. The handle was finished to a fine satin and seemed to be buffed with a wax. It has a tear drop section, and despite not being particularly thick, seems to fit well in the hand, and should index nicely.

The sheath is also the classic black and red backsewn Tommi sheath, made out of 3mm thick Veggie tan leather. It has a box style lesta, the front of which is made out of thin ply to help prevent breakage, and the back carved from Alder with a beveled entrance.

The sheath is saddle stitched with synthetic thread, and the end of the stitching is properly back stitched, locked off and melted. The sheath has a perfect, snappy fit without being too tight. The leather was nicely dyed, and left unfinished for the user to treat as they like. I finished the sheath with a warm application of Obenauf’s LP.

First impressions were good. The bolsters had a few rogue scratches, and the wood of the handle nearest the pommel had shrunk slightly either during storage or transport (0.3mm + or -). The satin finish on the blade is a little uneven, and shows evidence of having been sanded by hand, and then buffed. The grinds are symmetrical from side to side, though the tip is ground slightly off center. This is something I’ve seen even from master smiths, and is easily corrected with sharpening going forward, and does not affect use. The edge itself would easily shave out of the box, with no irregularities.

I decided to fix the shrunken wood, and took the time to also polish the oxidization off of the bolsters and pommel. I decided to leave the file marks on the pommel, as I actually like them. It reminds me that it’s a hand made item, and doesn’t affect function at all. I actually kind of like the fact that it’s a sand cast and filed to shape pommel, rather than a machined pommel.

After that, I soaked the handle in my usual mix of mineral spirits (orange solvent would be better), tung oil and bees wax at about 65 degrees Celsius, until the bubbles stopped rising. This is a treatment I’ve used on most of my wooden handles, and has held up exceedingly well in the extremely dry summers, and extremely wet fall/winter here on Vancouver Island.

My initial impressions of the knife are that of an old school hand made knife. Solid, made to use, and a certain rugged beauty. The handle is a stereotypical, thin/narrow Tommi handle, but is a well done tear drop profile, which should index very well in the hand. The handle is also slightly longer than other Tommi’s I’ve owned, which should hopefully make it more comfortable in a reverse or chest lever grip where the pommel would otherwise dig into the palm.

Conclusions

Despite some minor aesthetic flaws out of the box (which were easily corrected), this puukko has proven to be an absolute workhorse of an allrounder, excelling at deep, planing cuts, without losing too much finesse. The edge held up outstandingly well, and in spite of all of the torquing, scraping cuts I made, the edge suffered zero damage, and easily stropped back to its original hair whittling edge. Having used K510 previously, the heat treat on this blade seems very well done.

Having had to use a number of different grips, this handle has proven to be excellent. With a tear drop profile and decent palm swell, it indexed beautifully and not once did it twist in the hand or cause me to readjust my grip due to discomfort.

Ultimately, Pentti Kaartinen’s Arki-Tommi has quickly risen to among my favorites, and I’m glad I own it. I believe it is a perfect contender for an everyday puukko, as the name implies, and also carries with it a certain handmade charm that I personally appreciate.

“Rautalampi” literally means “iron pond”, which might refer to an ancient site for the extraction of bog iron, but apparently there is no historical references about it in that area, plus medieval toponyms were different than current ones and Rautalampi municipality was firstly founded in 1561, well beyond bog iron period of use.

In 1654 private soldier Martti Marttinen (Måns Mårtensson) borded the Eagle sailing ship and emigrated from Rautalampi to the colony of New Sweden, in nowadays Delaware.

In 1725 John Morton, Marttinen grandnephew, was born.

At the age of 31 he was elected to the Pennsylvania Assembly and as a representative of the state assembly he was a delegate to the Stamp Act congress in 1765. He would become Speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly and would e also voted to be delegate in both the First and Second Continental Congresses.

On the 2nd of August 1776, during the signing of the Declaration of Independence, he provided the swing vote without which independence would be doubtful.

Then Morton would take on his last role as Chairman of the Committee of the Whole, with the duty of drafting the articles of the Confederation, but he would die the 1st of April 1777, before the completion of the Articles and becoming the first signer to pass away. That’s it for some background about the town and notable people related to it.

We already dived in the past into the history of the namesake puukko, its creation in the 1890s by the hands of Emil Hänninen (1869-1952) and subsequent refining by master engraver Ivar Haring (1887-1954), thanks to a piece written by Jari Liukko and his father Arto who, in the 90s, actually resurrected the Rautalampi puukko, after forty years without a maker crafting it. Links to the puukko history and to Arto’s bio are the followings

https://nordiskaknivar.wordpress.com/2013/02/16/rautalammi-puukko/ https://nordiskaknivar.wordpress.com/2019/05/16/arto-liukko/

blade

length – 97 mm

wideness – 16 mm

thickness – 3,2 mm at the spine; 3,6 mm at bevels junction

tang – 3×3 mm at the pommel

steel – ThysseKrupp 80CrV2

bevels – flat

edge angle – 17°

edge hardness – ~ 61 HRC

handle

length – 101 mm

wideness – 24 mm max.

thickness – 19,5 mm max.

weight

knife – 70 g

with sheath – 100 g

The blade has been forged with hand held hammer from a bar of 80CrV2. It has a bland rhombic section and a ricasso, it’s slightly tapered in height and just a hair in thickness. After annealing and normalization it was heated with blowtorch, quenched in oil and tempered in oven. During the oil dipping the spine has been kept over the surface so to remain softer. Bevels are grinded at 17°, almost to zero.

The handle is made of curly birch with a 34 mm long nickel silver ferrule and a 10 mm long pommel. The wood has been filed so to embed inside the ferrule. The tang is tightly peened over the pommel, keeping the knife together without glue. The pommel has been worked and decorated entirely by file.

The handle is sanded with a fine grit, it’s quite tapered in height and thickness towards the blade, it has an oval section and, though not being particularly thick, fits well in the hand.

The sheath is hand stitched from 1,5 mm thick cowhide. Inside it has an alder liner, carved and sanded. The decorations were partly applied with stamps and partly engraved, when the leather started drying. The belt loop is closed by a nickel steel button, stamped with Liukko initials and attached to a steel ring. The friction retention is excellent.

In use

The puukko is slightly handle heavy, with the point of balance basically overlapping the junction between the ferrule and the wood.

Let’s start with a beech owl. No resistance when roughing out the two main facets, nor when carving the facial discs. The combination of blade thickness and relative wideness allowed for a very fast and easy work of the ear tufts, scooping a concave surface over he head.

There was a slight resistance when cutting all around the shaft to thin it down and break off the own, then just a little effort in planing the base flat.

At the end of the work the edge was pristine, with just a little loss of the shaving bite, but still plenty adequate. Six passes on Work Sharp green compound.

Let’s continue with a plane wood spikkentroll. I felt a hint of resistance while flattening a knot on the back, then no problem in roughing out and refining the hat. The puukko was extremely effective and fast in carving the hat notch, had a hair of resistance in doing the very fist cut to establish the face notch, then nothing to signal in the following carving and deepening of it. There has been some minor resistance while doing the first shaft thinning cuts, progressively disappeared the deeper I got into the wood. Nothing to signal when flattening the base.

A the end of the work the edge was pristine, with some minor bite loss. Fifteen passes on Work Sharp green compound.

Now it’s time for the plane wood wizard. I had a minor resistance while roughing the base facets, disappeared while finishing them. No problem establishing the three V marking the eyes, the nose and the mouth. The tip then worked excellently for engraving the nose profile grooves and well for carving the lower lip. No resistance this time while shaft thinning and no problem while flattening the base.

At the end of the work I found a 6 mm microroll near the handle, nevertheless the edge was still shaving without pressure for all its length. Six passes on fine ceramic rod to re-align the edge, then ten passes on Work Sharp green compound.

Let’s finish with a spatula. At the moment I don’t have my usual silver fir, so I had to opt for ayous, an extremely easy to access (in Italy at least) African straight grained and rather soft wood, comparable to the density and hardness of ash.

Although I always felt a small amount of resistance, compared to fir, the puukko kept its aggressive bite at all times, whatever I was working along the fibers on the spatula spine or against them to shape the front of the paddle. To obtain the lower hollow part of the shaft I did a stop cut midway and worked first from the paddle towards it, almost completely with pull cuts, than from the pommel to the stop cut, again mostly by pulling the knife. That was actually rather long and repetitive, but it allowed to really go the distance in searching, in vain, if the handle was to become uncomfortable. Nothing relevant to signal during finishing cuts and pull cuts to round the corners.

Throughout the work the cuts surface has been glossy and no perceivable bite loss was detected.

At the end the edge was pristine, the shaving bite was just a little less aggressive, but still clearly there. Fifteen passes on BRKT green compound.

Conclusions

Despite being a festive model, the Rautalampi is remarkably practical in wood carving and whittling, thanks to its slimness, excellent in tiny spaces, but paired with enough mass so to avoid any particular struggle when the need come for the removal of bigger amount of material while firstly roughly shaping a project.

It has happened a few times, when the project requested me to frequently shift grip, that the decorative grooves on the pommel felt a bit uneasy on the hand, but that was fast solved gripping the knife just a couple of mm forward. Another thing that may require a little time to get accustomed to is the perfectly symmetrical oval handle which doesn’t give any hint of edge placement to the muscular memory.

The use of ayous wood, new to me, made me slightly cautious about the heat treatment and fact that the puukko is held together solely by peening, but ultimately I was proven wrong and extremely pleased by both.

Posted in Uncategorized

… I will post a review featuring a few puukkos by different bladesmiths, like we already did a while ago.

As for now, here is a couple of sneak pics of the first puukkos I got my hands on. More will come.

Posted in Uncategorized

“My name is Antti Silvennoinen and I’m 57 years old. I live in small town called Mäntyharju in South Savo, Finland. I’m a carpenter and construction worker, I’ve also worked as instructor at the local workshop and I’ve arranged a carving course for children. I’ve practiced carving and wood work since I was six years old when I got my first puukko, which have hooked me on knives and carving ever since.

My grandmother had a huge influence on my enthusiasm for handicrafts: during the childhood summers I spent with her in the countryside, she let me carve as much as I wanted, got me all the wood and supplies I ever needed and encouraged me on my hobby.

People in the old days were very skilled and inventive as there wasn’t a shop at every corner where you could get everything, thus having to craft from themself a lot of what they needed. So I’ve always been also interested in used tools, crafting of consumables, constructions, fishing gear etc.

I crafted my first puukko in the first 80s when I was attending handicraft and artistic school in Lempäälä. During the forging course I made a couple of knife blades and chisels. Then, for about twenty years I crafted some knives buying the blades elsewhere. In the early 2000s I participated for three years to knife making courses held by Taisto Kuortti: he’s been my biggest inspirer to puukko making and his thorough and professional teaching has given me good capabilities in knifemaking. He also encouraged me to join the Suomen puukkoseura and to participate to the Fiskars competition. After the courses I made myself a forge and started seriously hammering steel.

Apparently I’ve inherited my handicraft skills from my grandfather, who was a skilled blacksmith, carpenter and construction worker, but unfortunately I don’t remember him, since I was only two years old when he passed away. Nevertheless I’ve seen some of his works and heard stories about him, then, a couple years ago, I got his anvil which hadn’t been used in over fifty years.

Knife making is currently a hobby of mine, besides woodworking, fishing and music: I play the guitar and create a lot of my fishing gears myself.

When making knives I’m fascinated by the diversity and possibilities you can get by combining steel, wood, leather, bark etc, leading to both aesthetic and working items. But you’re never completely done in knifemaking, there’s always something new to learn!

For my blades I use traditional carbon steel, recycled steel, silver steel, 80CrV2 plus some stainless steel. For the handles I use curly birch, birch burl, birch bark, moose antler plus a small amount of oak, mahogany etc. Almost every bolster is made with recycled materials.

I don’t have a traditional smithy or a workshop: I forge all my blades during the summer at our cottage, then I craft handles, sheath liners and bolsters. In winter I finish the knives and sew the sheaths in the apartment. I try to use power tools as little as possible, so for my knives to be really hand crafted. Beside traditional puukkos I also crafts filleting knives, leukus and hunting models. I like clean lines in my works and the more I craft, the simpler and leaner my knives have become.”

As I will post the review of a Rautalampi puukko in the near future I though it could be useful showing beforehand how this style came to be, evolving from the Kauhava festive models. We already wrote about the Rautalampi in the past https://nordiskaknivar.wordpress.com/2013/02/16/rautalammi-puukko/

but on this occasion I will go for side by side pictures.

Both puukkos were vrafted by master bladesmith Arto Liukko, following styles common in the 1890s. In particular the Kauhava follows Juho Lammi’s measures, while the Rautalampi follows Emil Hänninen ones.

It’s worth mentioning that Lammi handles were slightly thicker than those crafted by his cousin Iisakki Järvenpää. In the pictures you’ll see the Kauhava with brass fittings and dyed birch handle next to the Rautalampi with nickel silver fittings and oiled birch handle.

Federico Buldrini

Kauhava

blade

length – 97 mm

wideness – 15 mm

thickenss – 2 mm at the spine; 3,2 mm at the bevels junction

tang – 4×2 mm

edge angle – 19°

handle

length – 107 mm

wideness – 23 mm max.

thickness – 16 mm max.

weight

knife – 60 g

w/sheath – 92 g

Rautalampi

blade

length – 97 mm

wideness – 16 mm

thickenss – 2,5 mm at the spine; 3,5 mm at the bevels junction

tang – 3×3 mm

edge angle – 18°

handle

length – 101 mm

wideness – 24 mm max.

thickness – 19,5 mm max.

weight

knife – 70 g

w/sheath – 100 g

By Federico Buldrini

Since the subject is so broad and the reference material not always so easy to find, I will limit myself to discuss the broken back profile only in its western context.

We can find blades with strongly clipped points or spines abruptly angled in razors, knives and folders Greeks and Romans, as early as the 4th century BCE. However the profile isn’t quite what we’re searching for here, since the majority, fixed blades especially, were more like scaled down versions of kopis, sica and falcata swords.

According to German historiography the very first examples of knives classifiable as seaxes are also dated around the 4th century BCE and seem to come from Swedish Skåne, at the time inhabited by what are considered to be the first clans of the Lombards. With the migration towards south the knife then spread across the Alemanni tribes north of the Main river, then towards the Danube and finally west reaching France.

Still these knives didn’t have our profile of interest, on the other hand keeping the spine straight or just dropped enough to form a spear point, usually around the central axis of the blade. This last type of profile will be also very common in Frankish scramasax, with some exceptions.

A medium sized blade with a profile nearing our subject is among the findings from the Pictish burials of Rhyne, dated to the 5th-6th century CE.

Knives with an increasingly marked broken back profile were found in the Vendel period (450-790) ship burials in Sutton Hoo, England and their Swedish counterparts in Uppsala and, precisely, Vendel.

The similarities in the types of burials, the objects, the style of decorations and metallurgy techniques among findings from Vendel, Uppsala and Sutton Hoo has led some scholars to theorize that the warriors buried may had been part of a specific caste or, more likely, a brotherhood of arms.

It has to be said that the broken back knives from the Vendel period were seldom seax, but rather small to medium sized belt knives in male graves and brooch knives in female graves.

However in Finland it has been recently discovered a Vendel period seax with a blade already leaning towards a style similar to what will eventually evolve in the British Islands,

while in the Aachen cathedral is kept a broken back seax, dated to the 8th century, called “Charlemagne hunting knife”, but without any real proof of its actual owner.

The broken back profile, in this case called Hedeby type 6, is the second most common among the knives and blades found in Heiðabýr, today in German Jutland, while part of the Danish kingdom during the Viking Age (790-1066) and from here probably spread in the south of Sweden and Norway, while becoming less common towards the norther regions.

Also, a good number of such blades, but with the spine angle changing already before half its length, has been found in Jórvík, nowadays York, established in 867 by Halfdan Ragnarsson, following the conquest by the Great Heated Army, led by Ivar the boneless, of the Anglosaxon harbor of Eoforwic, in turn built over the Roman Eburacum. In this case too the knives are usually middle to small sized.

Folding knives with a central pivot and blades with a broken back point on one side and a spear point of the other, probably used by leather workers have been found in England, at Jórvik, Canterbury and London and in Russia, at Novgorod. All the findings are dated from the 10th to the 12th century.

Around the year 1000, while in continental Europe the seax had started to loose popularity, Anglosaxon perfected its English counterpart, by many considered to be the maximum expression of this knife though somewhat influenced by the later Frankish ones. Anyway is undeniable that some Anglosaxon specimen shows a level of metallurgic and decorations complexity rarely seen elsewhere.

Some 10th century seaxes found in Dublin are particularly interesting, on the other hand, for their strongly clipped point, almost anticipating the 17th century Spanish navajas.

To conclude, Anglosaxon seaxes, regardless of their size, have a doubly tapering spine, thickening towards the hunch and then thinning towards the tip.

Anyway with the end of the 12th century seaxes were completely set aside on the British Islands too.

From this point on a kind of broken back profile, but way more leaning towards a sharply clipped point was adopted continuously until the 16th century on various declinations first on the falchion

and on to the messer

both being single edged swords utilized primarily, but not exclusively by infantry soldiers. In the same period, but in civil context, were developed the bauernwehr, big hunting knives from Germany and Bohemia, sometimes the size of a small sword and, especially in these cases, very similar to a messer without a cross guard.

After the Muslim conquest of Spain in 711 new weapons were introduced in souther Europe. Scimitars, jambiya daggers and generally curved bladed weapons were called alfanje in Spanish and this name ended up being used also to describe similar swords manufactured by Spaniards. Following Spanish and Muslim trades around the Mediterranean Sea, especially with the Venetian Republic, these swords were appreciated and forged outside of Spain and gave origin to the Italian storta, the southern counterpart to the falchion and messer of central and northern Europe.

Between 1600 and 1700 Europe saw the growth of industrial production of folding knives and some of these, English penny knives in particular, already in 1650 had blades with such a strong broken back profile which almost eliminated completely the point. It’s quite safe to assume that these blades will be the base for the sheepsfoot and lambsfoot profiles.

As for the western folders, from the 17th century on, those knives that had an actual point and a straight spine shifted towards more elegant and softened profiles. Such examples are the Savoyard knives, both Italian and French, the Laguiole, the Spanish navajas, all somewhat influenced by the shape of the Ottoman yatagan sword. From these knives will evolve the modern clip point and texas toothpick profiles.

Meanwhile in the United States of America, since 1785, existed the barlow knife which, compared to its European counterparts and had a very strong profile.

In the last years of 1600, after the establishment in 1670 of the Hudson Bay Fur Trade Company, Sheffield’s knife factories were commissioned with the creation and production of a camp knife to be issued to the hunters and trappers working for the Company. The namesake knife,

which profile reworks the Anglosaxon seax, will remain in production until the 1820s, when it was eventually replaced by butcher knives first and by English made bowie knives then.

With the end of 19th century the broken back profile has almost disappeared. Beside historical replicas, few contemporary declinations are the Varusteleka Skrama, the Morakniv steak knives, which sport a very Jórvik styled blade and, somewhat similar to the Pictish blades of Rhyne, the Mora knife classical profile, firstly introduced in 1891 by Frost-Erik Ernström.

Posted in Uncategorized

I am very happy to report that Anssi Ruusuvori’s new English language book is available. Sometime ago there was a post on this blog about Annsi profiling his background as puukkoseppä and historian. I would encourage you to read it: https://nordiskaknivar.wordpress.com/2012/11/25/anssi-ruusuvuori-puukkoseppa-historian-and-author/

The new book, The Puukko: Finnish Knives from Antiquity to Today is available on Amazon https://www.amazon.com/Puukko-Finnish-Knives-Antiquity-Today/dp/0764360701 Here is the introduction;

“For a Finn, the puukko is the most important tool and at the same time the most feared weapon. You could almost say the puukko has the same importance for a Finn as the samurai sword has for the Japanese. It is a 2,000-year-old mystical weapon that has been used for centuries with the same conviction and dexterity during times of peace and war. This comprehensive resource on the Finnish puukko is the only one available and covers the history and the various types by using extensive photos of examples. Anssi Ruusuvuori has reprocessed the history of this remarkable knife type in a form unique up to now. He deals with technical and design aspects of the puukko and guides the reader through the history of this legendary tool and weapon from the Viking era up to the present. He reports about the great master smiths of industrialization in the late 19th century and about rediscovering the puukko in the recent past. This book’s initial focus is on the puukko’s technology and history. In the second section, the author introduces the different puukko types according to their materials and construction. Thereafter are presented the multiple regional types and special puukkos, which are essential to know about as a collector and knife enthusiast. This book provides a comprehensive overview with respect to the topic “puukko” and transfers a rich treasure of knowledge. During its long history, the puukko was used for a great diversity of tasks, such as the production of ladles and other household tools; the carving of ornaments; scratching ice off cart wheels; cutting food; gutting and skinning of game, fish, or livestock; climbing out of an ice hole back to firm ground; and magic rituals (to protect children from evil spirits, to pray for a good harvest, and so on). It was used for self-defense and for duels. The main source of material for this book is the puukko collections of Finnish museums and private collectors. The greater part of researched knives is from the National Museum of Finland. Additional material was gathered from the Kauhava Puukko Museum, the Peura Museum, the Turku Regional Museum, the Aboa Vetus et Ars Nova Museum, the Ostrobothnian Museum, the Museum of Crime, and various private collections.”

His earlier masterwork in Finnish (Puukon Historia, Puukon Historia 2) will also be reprinted before the end of the year by http://Readme.fi. and is available for preorder by email at joni@pyysalo.

Anssi has been a very good friend to Nordiska Knivar providing information whenever I made a request. Do yourself a favor, gain some knowledge and read Annsi’s new book. In the meantime here is a selection of some of his new work. Enjoy!